Lesson 14 - Super Resolution; Image Segmentation with U-Net

These are my personal notes from fast.ai course and will continue to be updated and improved if I find anything useful and relevant while I continue to review the course to study much more in-depth. Thanks for reading and happy learning!

Topics

- Super resolution.

- A technique that allows us to restore high resolution detail in our images, based on a convolutional neural network.

- In the process, we'll look at a few modern techniques for faster and more reliable training of generative convnets.

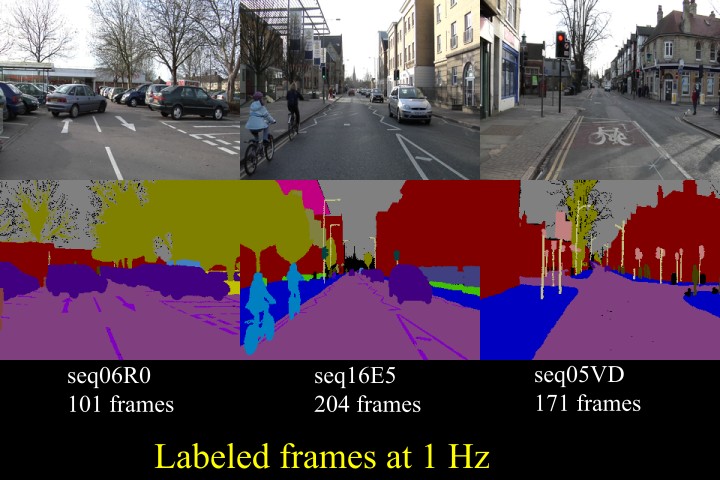

- Image segmentation.

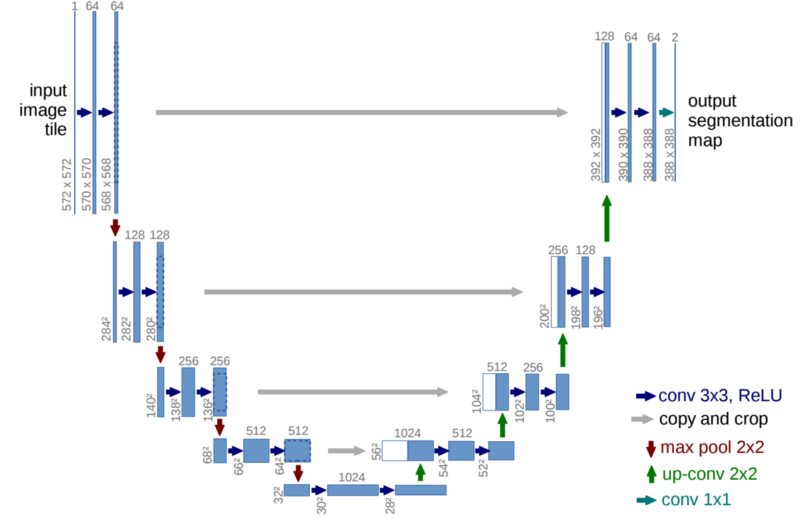

- U-Net architecture.

- A state of the art technique that has won many Kaggle competitions and is widely used in industry.

- Image segmentation models allow us to precisely classify every part of an image, right down to pixel level.

- U-Net architecture.

Lesson Resources

- Website

- Video

- Wiki

- Jupyter Notebook and code

- Dataset

- ImageNet sample in files.fast.ai/data / direct download link (2.1 GB)

- Full ImageNet [faster download from Kaggle, mirrored over from the ImageNet Download Site]

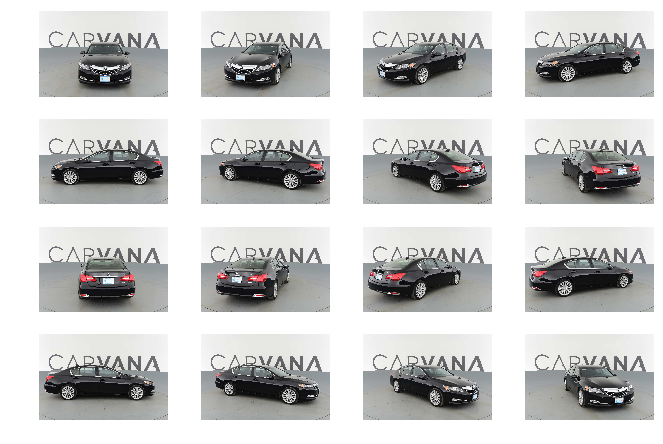

- Kaggle Carvana Image Masking competition - you can download it with Kaggle API as usual

Assignments

Papers

- Must read

- Perceptual Losses for Real-Time Style Transfer and Super-Resolution by Justin Johnson, et al.

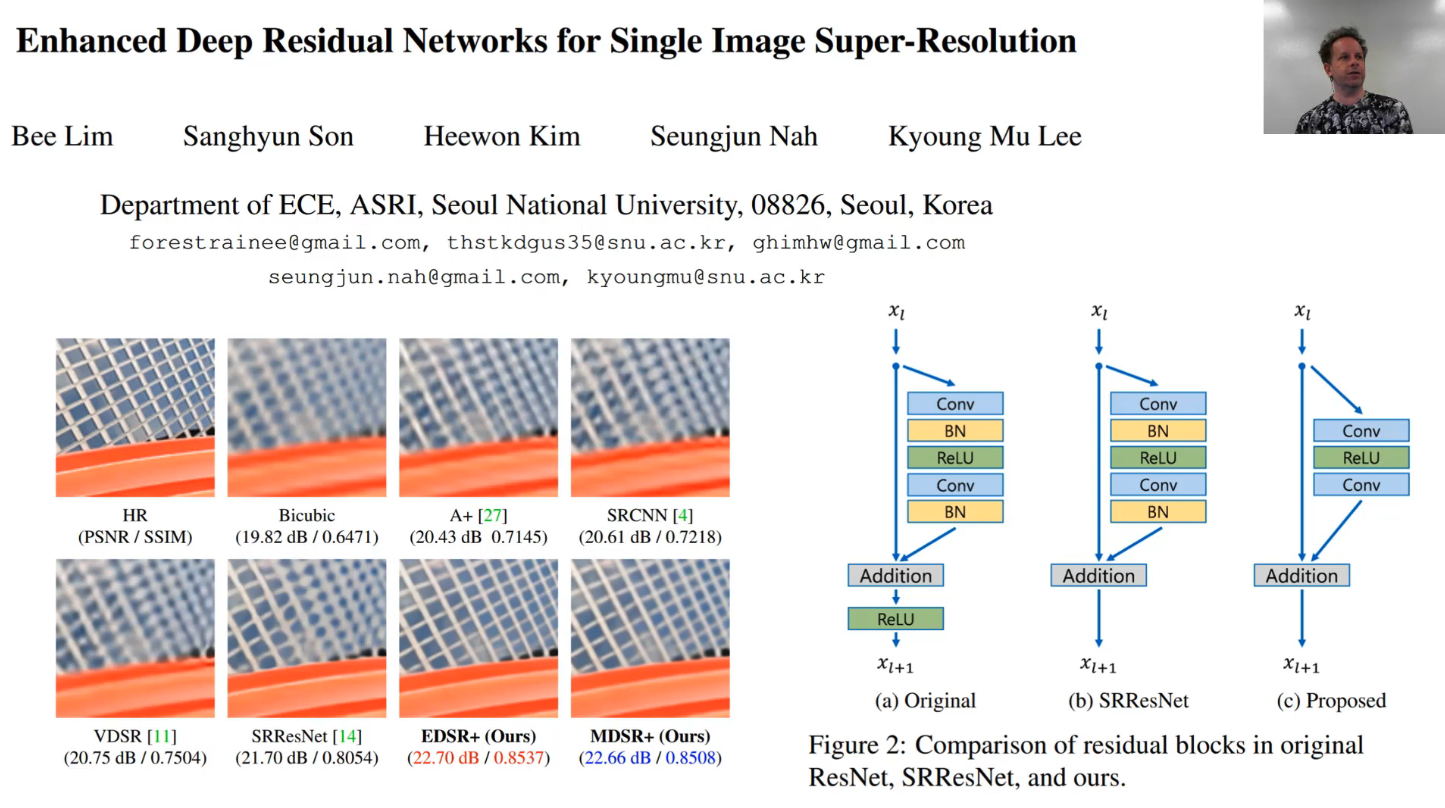

- Enhanced Deep Residual Networks for Single Image Super-Resolution (EDSR) by Bee Lim, et al.

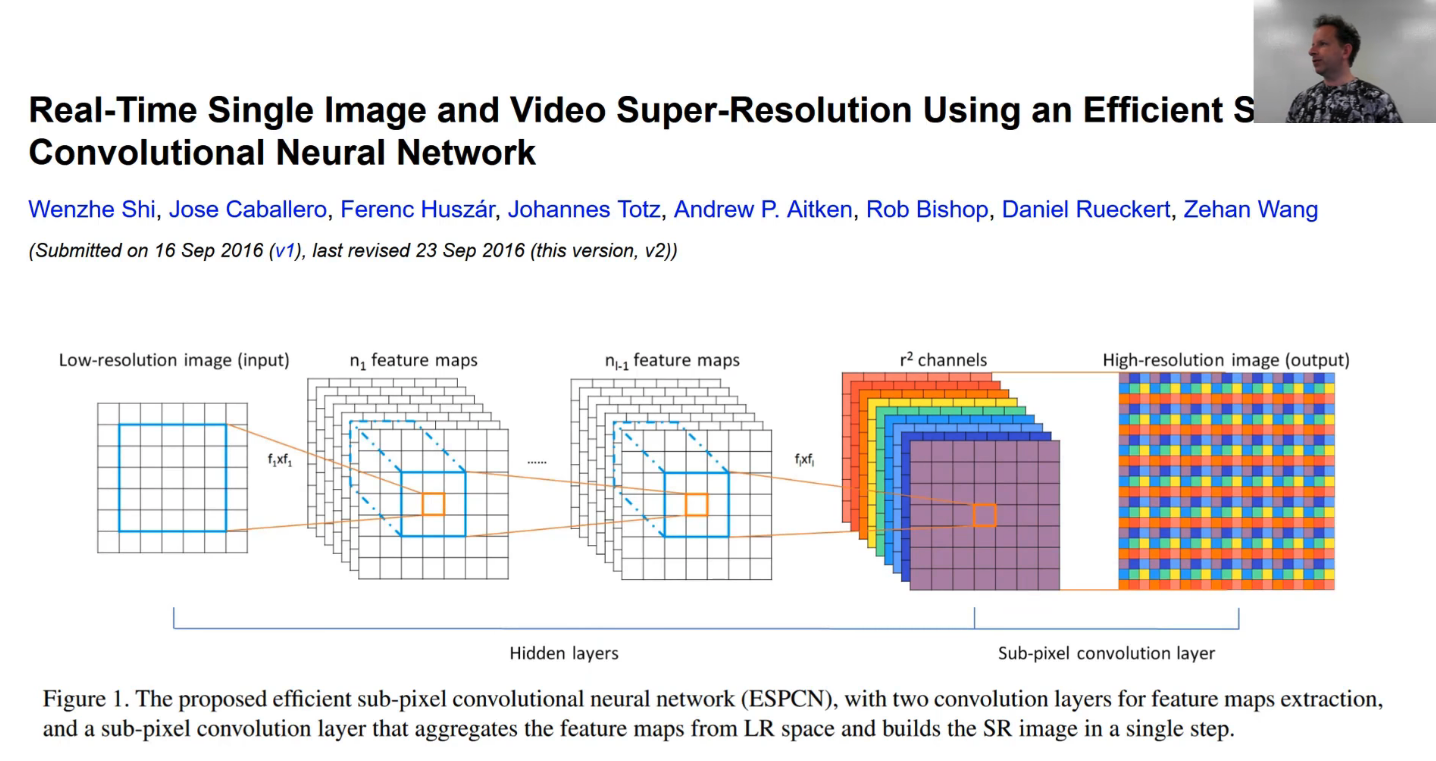

- Real-Time Single Image and Video Super-Resolution Using an Efficient Sub-Pixel Convolutional Neural Network by Wenzhe Shi, et al.

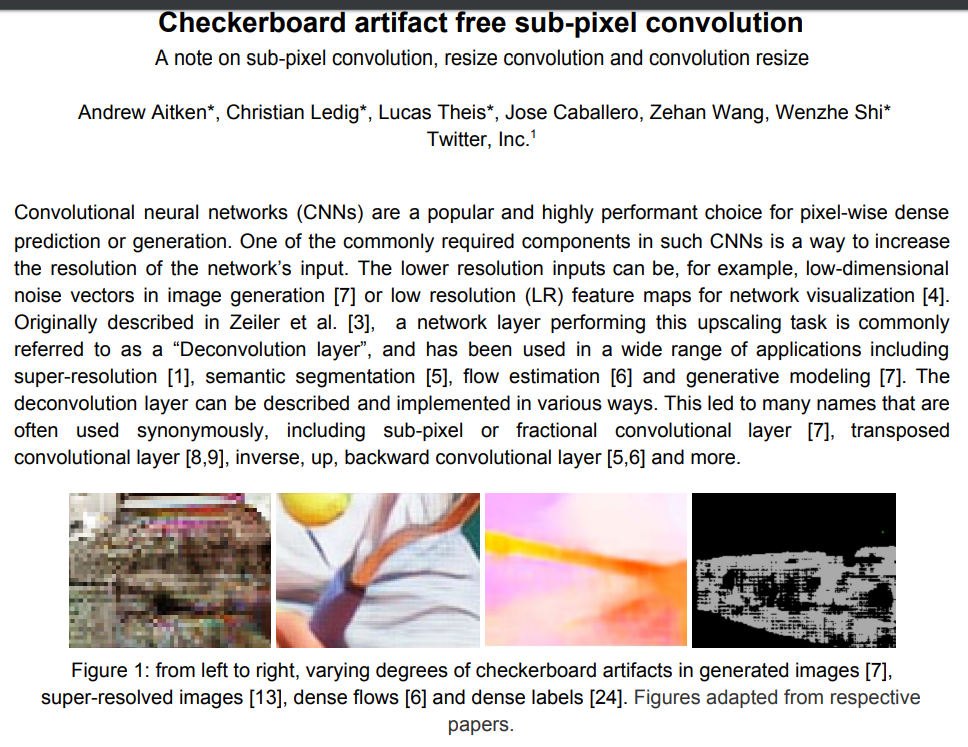

- Checkerboard artifact free sub-pixel convolution: A note on sub-pixel convolution, resize convolution and convolution resize by Andrew Aitken, et al.

- U-Net: Convolutional Networks for Biomedical Image Segmentation by Olaf Ronneberger, et al.

- Additional papers (optional)

- Feature Pyramid Networks for Object Detection by Tsung-Yi Lin, Piotr Dollar, Ross Girshick, Kaiming He, et al.

My Notes

Show and tell from last week

Alena Harley did something really interesting which was she tried finding out what would happen if you did CycleGAN on just three or four hundred images and I really like these projects where people just go to Google Image Search using the API or one of the libraries out there. Some of our students have created some very good libraries for interacting with Google images API to download a bunch of stuff they are interested in, in this case some photos and some stained glass windows. With 300~400 photos of that, she trained a few different model — this is what I particularly liked. As you can see, with quite a small number of images, she gets very nice stained-glass effects. So I thought that was an interesting example of using pretty small amounts of data that was readily available that she was able to download pretty quickly. There is more information about that on the forum if you are interested. It's interesting to wonder about what kinds of things people will come up with with this kind of generative model. It's clearly a great artistic medium. It's clearly a great medium for forgeries and fakeries. I wonder what other kinds of things people will realize they can do with these kind of generative models. I think audio is going to be the next big area. Also very interactive type stuff. Nvidia just released a paper showing an interactive kind of photo repair tool where you just brush over an object and it replaces it with a deep learning generated replacement very nicely. Those kinds of interactive tools, I think would be very interesting too.

Super Resolution [00:02:06]

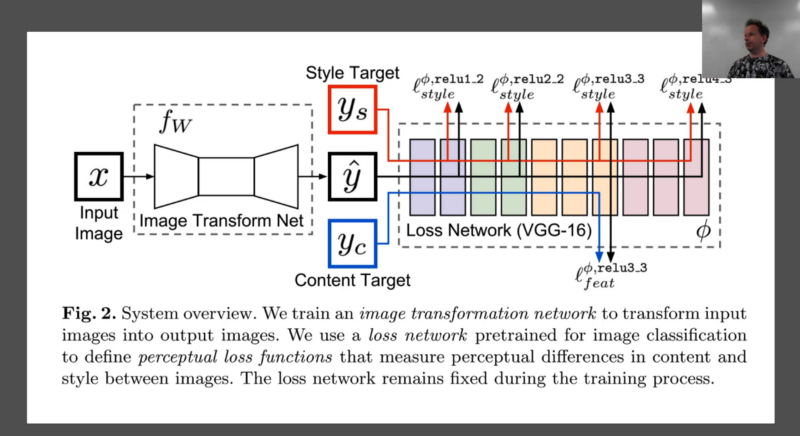

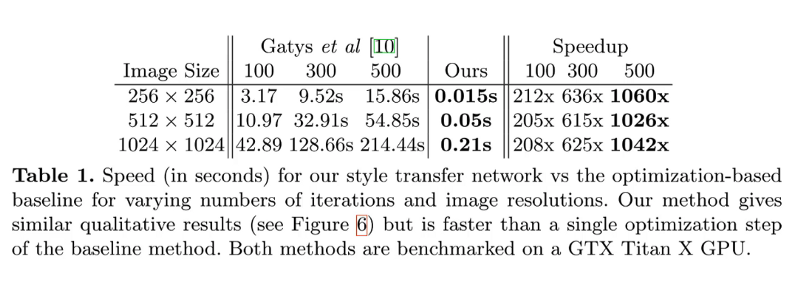

Perceptual Losses for Real-Time Style Transfer and Super-Resolution paper

Last time, we looked at doing style transfer by actually directly optimizing pixels. Like with most of the things in part two, it's not so much that I'm wanting you to understand style transfer per se, but the kind of idea of optimizing your input directly and using activations as part of a loss function is really the key takeaway here.

So it's interesting then to see effectively the follow-up paper, not from the same people but the paper that came next in the sequence of these vision generative models with this one from Justin Johnson and folks at Stanford. It actually does the same thing — style transfer, but does it in a different way. Rather than optimizing the pixels, we are going to go back to something much more familiar and optimize some weights. So specifically, we are going to train a model which learns to take a photo and translate it into a photo on this in the style of a particular artwork. So each conv net will learn to produce one kind of style.

Now it turns out that getting to that point, there is an intermediate point which (I actually think more useful and takes us half way there) is something called super resolution. So we are actually going to start with super resolution [00:03:55]. Because then we'll build on top of super resolution to finish off the conv net based style transfer.

Super resolution is where we take a low resolution image (we are going to take 72 by 72) and upscale it to a larger image (288 by 288 in our case) trying to create a higher res image that looks as real as possible. This is a challenging thing to do because at 72 by 72, there's not that much information about a lot of the details. The cool thing is that we are going to do it in a way as we tend to do with vision models which is not tied to the input size so you could totally then take this model and apply it to a 288 by 288 image and get something that's four times bigger on each side so 16 times bigger than the original. Often it even works better at that level because you're really introducing a lot of detail into the finer details and you could really print out a high resolution print of something which earlier on was pretty pixelated.

Notebook: enhance.ipynb [00:05:06]

It is a lot like that kind of CSI style enhancement where we're going to take something that appears like the information is just not there and we kind of invent it — but the conv net is going to learn to invent it in a way that's consistent with the information that is there, so hopefully it's inventing the right information. One of the really nice things about this kind of problem is that we can create our own dataset as big as we like without any labeling requirements because we can easily create a low res image from a high res image just by down sampling our images. 🔖 So something I would love some of you to try this week would be to do other types of image-to-image translation where you can invent "labels" (your dependent variables). For example:

- Deskewing: Either recognize things that have been rotated by 90 degrees or better still that have been rotated by 5 degrees and straighten them.

- Colorization: Make a bunch of images into black-and-white and learn to put the color back again.

- Noise-reduction: Maybe do a really low quality JPEG save, and learn to put it back to how it should have been.

- Maybe taking something that's in a 16 color palette and put it back to a higher color palette.

I think these things are all interesting because they can be used to take pictures that you may have taken back on crappy old digital cameras before there are high resolution or you may have scanned in some old photos that are now faded, etc. I think it's really useful thing to be able to do and it's a good project because it's really similar to what we are doing here but different enough that you come across some interesting challenges on the way, I'm sure.

I'm going to use ImageNet again [00:07:19]. You don't need to use all of the ImageNet at all, I just happen to have it lying around. You can download the one percent sample of ImageNet from files.fast.ai. You can use any set of pictures you have lying around honestly.

matplotlib inline

%reload_ext autoreload

%autoreload 2

Super resolution data

from fastai.conv_learner import *

from pathlib import Path

# torch.cuda.set_device(0)

torch.backends.cudnn.benchmark = True

PATH = Path('data/imagenet')

PATH_TRN = PATH / 'train'

In this case, as I say we don't really have labels per se, so I'm just going to give everything a label of zero just so we can use it with our existing infrastructure more easily.

fnames_full, label_arr_full, all_labels = folder_source(PATH, 'train')

fnames_full = ['/'.join(Path(fn).parts[-2:]) for fn in fnames_full]

list(zip(fnames_full[:5], label_arr_full[:5]))

# -----------------------------------------------------------------------------

# Output

# -----------------------------------------------------------------------------

[('n01440764/n01440764_12241.JPEG', 0),

('n01440764/n01440764_529.JPEG', 0),

('n01440764/n01440764_11155.JPEG', 0),

('n01440764/n01440764_9649.JPEG', 0),

('n01440764/n01440764_8013.JPEG', 0)]

all_labels[:5]

# -----------------------------------------------------------------------------

# Output

# -----------------------------------------------------------------------------

['n01440764', 'n01443537', 'n01491361', 'n01494475', 'n01498041']

Now, because I'm pointing at a folder that contains all of ImageNet, I certainly don't want to wait for all of ImageNet to finish to run an epoch. So here, I'm just, most of the time, I would set "keep percent" (keep_pct) to 1 or 2%. And then I just generate a bunch of random numbers and then I just keep those which are less than 0.02 and so that lets me quickly subsample my rows.

np.random.seed(42)

keep_pct = 1.

# keep_pct = 0.02

keeps = np.random.rand(len(fnames_full)) < keep_pct

fnames = np.array(fnames_full, copy=False)[keeps]

label_arr = np.array(label_arr_full, copy=False)[keeps]

Architecture

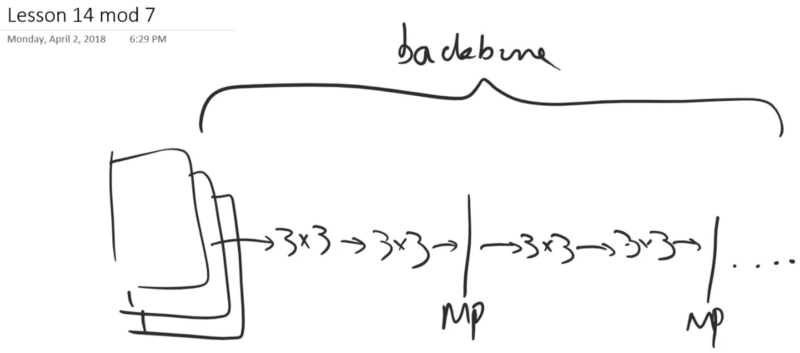

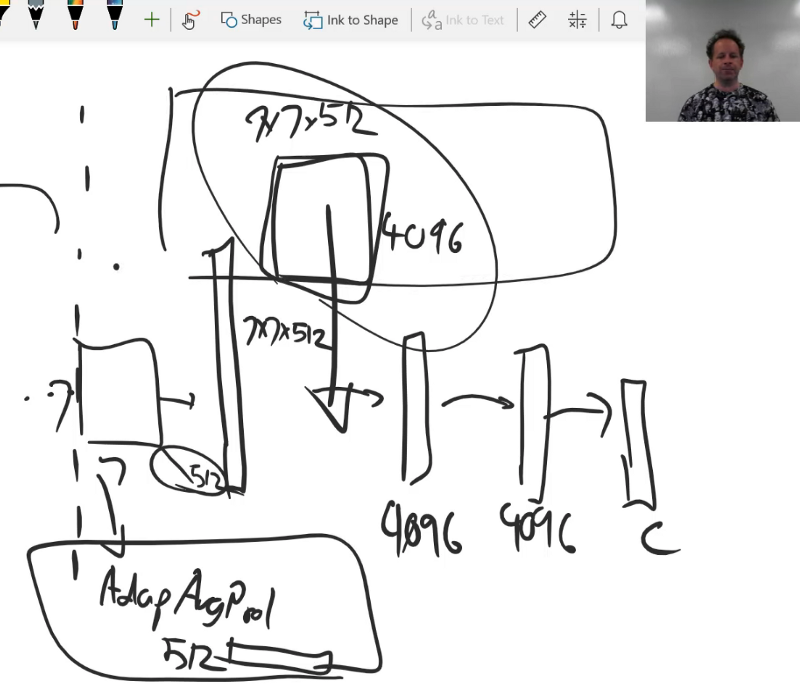

So we are going to use VGG16 [00:08:21] and VGG16 is something that we haven't really looked at in this class but it's a very simple model where we take our normal presumably 3 channel input, and we basically run it through a number of 3x3 convolutions, and then from time to time, we put it through a 2x2 maxpool and then we do a few more 3x3 convolutions, maxpool, so on so forth. And this is our backbone.

Then we don't do an adaptive average pooling layer. After a few of these, we end up with this 7x7x512 grid as usual (or something similar). So rather than average pooling, we do something different which is we flatten the whole thing — so that spits out a very long vector of activations of size 7x7x512 if memory serves correctly. Then that gets fed into two fully connected layers each one of which has 4096 activations, and one more fully connected layer which has however many classes. So if you think about it, the weight matrix here, it's HUGE 7x7x512x4096. It's because of that weight matrix really that VGG went out of favor pretty quickly — because it takes a lot of memory and takes a lot of computation and it's really slow. And there's a lot of redundant stuff going on here because really those 512 activations are not that specific to which of those 7x7 grid cells they are in. But when you have this entire weight matrix here of every possible combination, it treats all of them uniquely. So that can also lead to generalization problems because there's just a lot of weights and so forth.

Modern network approach

My view is that the approach that is used in every modern network which is here we do an adaptive average pooling (in Keras it's known as a global average pooling, in fast.ai, we do an AdaptiveConcatPool) which spits it straight down to a 512 long activation [00:11:06]. I think that's throwing away too much geometry. 🔖 So to me, probably the correct answer is somewhere in between and will involve some kind of factored convolution or some kind tensor decomposition which maybe some of us can think about in the coming months. So for now, anyway, we've gone from one extreme which is the adaptive average pooling to the other extreme which is this huge flattened fully connected layer.

Create something that's good at a lots of things

A couple of things which are interesting about VGG that make it still useful today [00:11:59]. The first one is that there's more interesting layers going on here with most modern networks including the ResNet family, the very first layer generally is a 7x7 conv with stride 2 or something similar. Which means we throw away half the grid size straight away and so there is little opportunity to use the fine detail because we never do any computation with it. So that's a bit of a problem for things like segmentation or super resolution models because the fine details matters. We actually want to restore it. Then the second problem is that the adaptive pooling layer entirely throws away the geometry in the last few sections which means that the rest of the model doesn't really have as much interesting kind of learning that geometry as it otherwise might. Therefore for things which are dependent on position, any kind of localization based approach to anything that requires generative model is going to be less effective. So one of the things I'm hoping you are hearing as I describe this is that probably none of the existing architectures are actually ideal. We can invent a new one. Actually, I just tried inventing a new one over the week which was to take the VGG head and attach it to a ResNet backbone. Interestingly, I found I actually got a slightly better classifier than a normal ResNet but it also was something with a little bit more useful information in it. It took 5 or 10% longer to train but nothing worth worrying about. Maybe we could, in ResNet, replace this (7x7 conv stride 2) as we've talked about briefly before. This very early convolution with something more like an Inception stem which has a bit more computation. I think there's definitely room for some nice little tweaks to these architectures so that we can build some models which are maybe more versatile. At the moment, people tend to build architectures that just do one thing. They don't really think what am I throwing away in terms of opportunity because that's how publishing works. You published "I've got state of the art of this one thing rather than you have created something that's good at a lots of things.

For these reasons, we are going to use VGG today even though it's ancient and it's missing lots of great stuff [00:14:42]. One thing we are going to do though is use a slightly more modern version which is a version of VGG where batch norm has been added after all the convolutions. In fast.ai when you ask for a VGG network, you always get the batch norm one because that's basically always what you want. So this is VGG with batch norm. There is 16 and 19, the 19 is way bigger and heavier, and doesn't really do any better, so no one really uses it.

arch = vgg16

sz_lr = 72

We are going to go from 72 by 72 LR (sz_lr: size low resolution) input. We are going to initially scale it up by times 2 with the batch size of 64 to get 2 * 72 so 144 by 144 output. That is going to be our stage one.

scale, bs = 2, 64

# scale, bs = 4, 32

sz_hr = sz_lr * scale

We'll create our own dataset for this and it's very worthwhile looking inside the fastai.dataset module and seeing what's there [00:15:45]. Because just about anything you'd want, we probably have something that's almost what you want. So in this case, I want a dataset where my x's are images and my y's are also images. There's already a files dataset we can inherit from where the x's are images and then I just inherit from that and I just copied and pasted the get_x and turn that into get_y so it just opens an image. Now I've got something where the x is an image and the y is an image, and in both cases, what we're passing in is an array of files names.

class MatchedFilesDataset(FilesDataset):

def __init__(self, fnames, y, transforms, path):

self.y = y

assert(len(fnames) == len(y))

super().__init__(fnames, transform, path)

def get_y(self, i): return open_image(os.path.join(self.path, self.y[i]))

def get_c(self): return 0

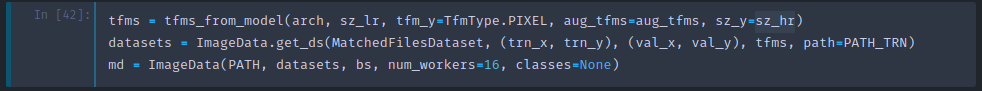

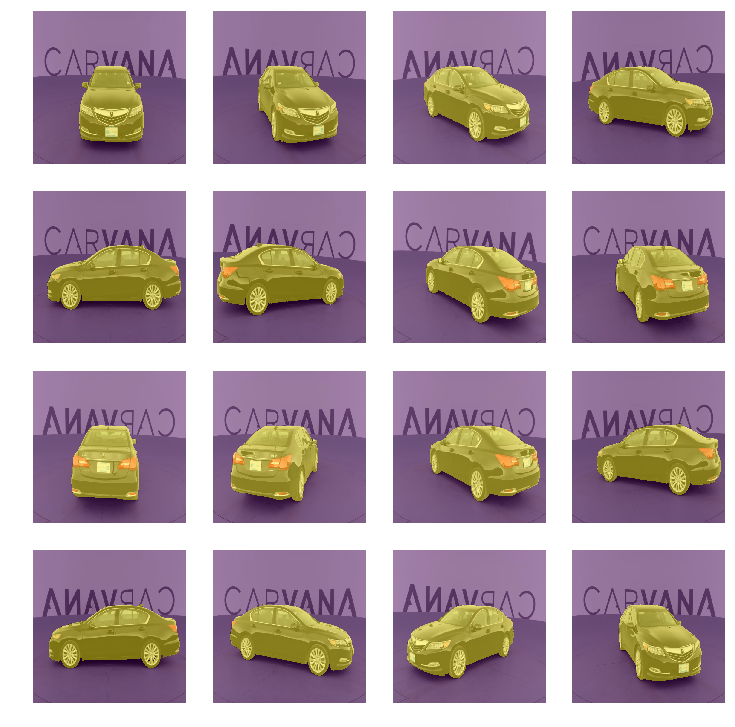

I'm going to do some data augmentation [00:16:32]. Obviously with all of ImageNet, we don't really need it but this is mainly here for anybody who is using smaller datasets to make the most of it. RandomDihedral is referring to every possible 90 degree rotation plus optional left/right flipping so they are dihedral group of eight symmetries. Normally we don't use this transformation for ImageNet pictures because you don't normally flip dogs upside down but in this case, we are not trying to classify whether it's a dog or a cat, we are just trying to keep the general structure of it. So actually every possible flip is a reasonably sensible thing to do for this problem.

aug_tfms = [RandomDihedral(tfm_y=TfmType.PIXEL)]

Create a validation set in the usual way [00:17:19]. You can see I'm using a few more slightly lower level functions — generally speaking, I just copy and paste them out of the fastai source code to find the bits I want. So here is the bit which takes an array of validation set indexes and one or more arrays of variables, and simply splits. In this case, this (np.array(fnames)) into a training and validation set, and this (the second np.array(fnames)) into a training and validation set to give us our x's and our y's. In this case, the x and the y are the same. Our input image and our output image are the same. We are going to use transformations to make one of them lower resolution. That's why these are the same thing.

val_idxs = get_cv_idxs(len(fnames), val_pct=min(0.01 / keep_pct, 0.1))

((val_x, trn_x), (val_y, trn_y)) = split_by_idx(val_idxs, np.array(fnames), np.array(fnames))

len(val_x), len(trn_x)

# -----------------------------------------------------------------------------

# Output

# -----------------------------------------------------------------------------

(194, 19245)

img_fn = PATH / 'train' / 'n01558993' / 'n01558993_9684.JPEG'

The next thing that we need to do is to create our transformations as per usual [00:18:13]. We are going to use tfm_y parameter like we did for bounding boxes but rather than use TfmType.COORD we are going to use TfmType.PIXEL. That tells our transformations framework that your y values are images with normal pixels in them, so anything you do to the x, you also need to do the same thing to the y. You need to make sure any data augmentation transformations you use have the same parameter as well.

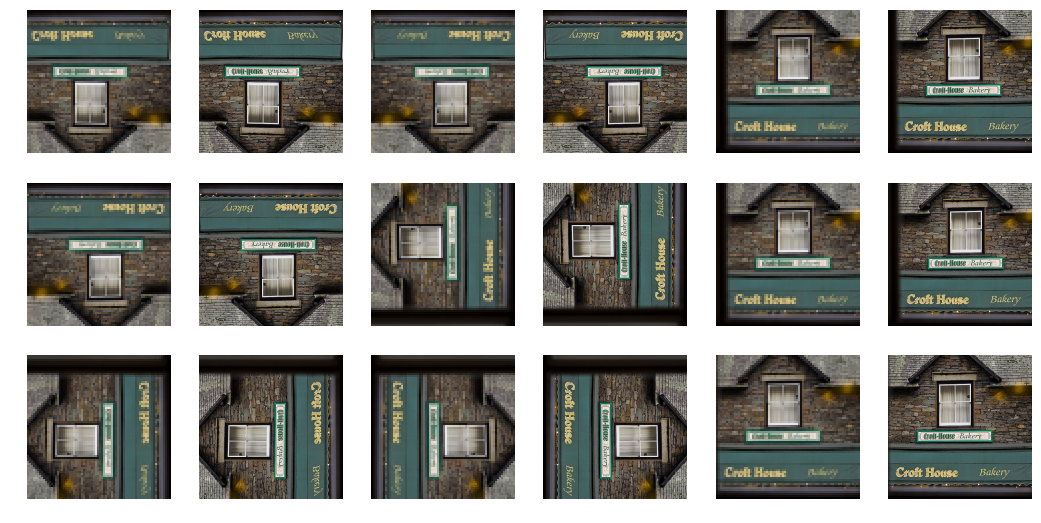

tfms = tfms_from_model(arch, sz_lr, tfm_y=TfmType.PIXEL, aug_tfms=aug_tfms, sz_y=sz_hr)

datasets = ImageData.get_ds(MatchedFilesDataset, (trn_x, trn_y), (val_x, val_y), tfms, path=PATH_TRN)

md = ImageData(PATH, datasets, bs, num_workers=16, classes=None)

You can see the possible transform types you got:

- CLASS: classification which we are about to use the segmentation in the second half of today

- COORD: coordinates — no transformation at all

- PIXEL

Once we have Dataset class and some x and y training and validation sets. There is a handy little method called get datasets (get_ds) which basically runs that constructor over all the different things that you have to return all the datasets you need in exactly the right format to pass to a ModelData constructor (in this case the ImageData constructor). So we are kind of going back under the covers of fastai a little bit and building it up from scratch. In the next few weeks, this will all be wrapped up and refactored into something that you can do in a single step in fastai. But the point of this class is to learn a bit about going under the covers.

Something we've briefly seen before is that when we take images in, we transform them not just with data augmentation but we also move the channel dimension up to the start, we subtract the mean divided by the standard deviation etc [00:20:08]. So if we want to be able to display those pictures that have come out of our datasets or data loaders, we need to de-normalize them. So the model data object's (md) dataset (val_ds) has denorm function that knows how to do that. I'm just going to give that a short name for convenience:

denorm = md.val_ds.denorm

So now I'm going to create a function that can show an image from a dataset and if you pass in something saying this is a normalized image, then we'll denorm it.

def show_img(ims, idx, figsize=(5,5), normed=True, ax=None):

if ax is None:

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=figsize)

if normed:

ims = denorm(ims)

else:

ims = np.rollaxis(to_np(ims), 1, 4)

ax.imshow(np.clip(ims, 0, 1)[idx])

ax.axis('off')

x, y = next(iter(md.val_dl))

x.size(), y.size()

# -----------------------------------------------------------------------------

# Output

# -----------------------------------------------------------------------------

(torch.Size([64, 3, 72, 72]), torch.Size([64, 3, 144, 144]))

You'll see here we've passed in size low res (sz_lr) as our size for the transforms and size high res (sz_hr) as, this is something new, the size y parameter (sz_y) [00:20:58]. So the two bits are going to get different sizes.

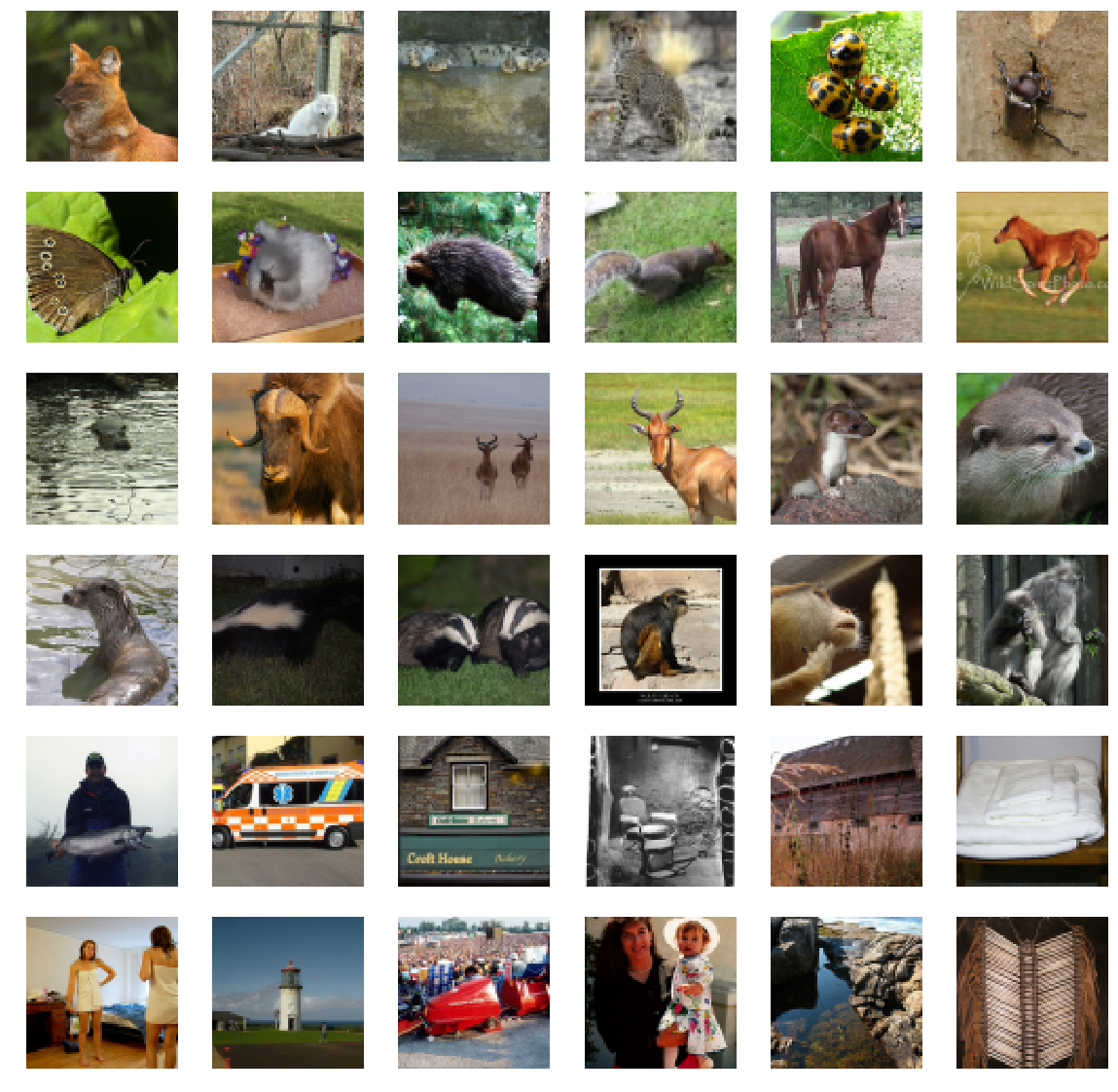

Here you can see the two different resolutions of our x and our y for a whole bunch of bakery.

idx = 61

fig, axes = plt.subplots(1, 2, figsize=(9, 5))

show_img(x, idx, ax=axes[0])

show_img(y, idx, ax=axes[1])

As per usual, plt.subplots to create our two plots and then we can just use the different axes that came back to put stuff next to each other.

batches = [next(iter(md.aug_dl)) for i in range(9)]

We can then have a look at a few different versions of the data transformation [00:21:37]. There you can see them being flipped in all different directions.

fig, axes = plt.subplots(3, 6, figsize=(18, 9))

for i,(x, y) in enumerate(batches):

show_img(x, idx, ax=axes.flat[i*2])

show_img(y, idx, ax=axes.flat[i*2+1])

Model [00:21:48]

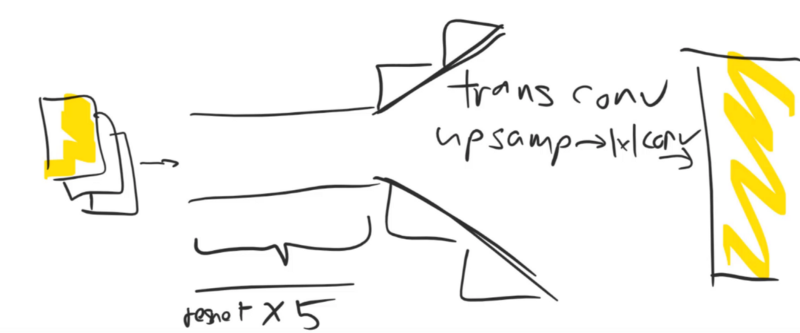

Let's create our model. We are going to have a small image coming in, and we want to have a big image coming out. So we need to do some computation between those two to calculate what the big image would look like. Essentially there're two ways of doing that computation:

- We could first of all do some upsampling and then do a few stride one layers to do lots of computation.

- We could first do lots of stride one layers to do all the computation and then at the end do some upsampling.

We are going to pick the second approach because we want to do lots of computation on something smaller because it's much faster to do it that way. Also, all that computation we get to leverage during the upsampling process. Upsampling, we know a couple of possible ways to do that. We can use:

- Transposed or fractionally strided convolutions

- Nearest neighbor upsampling followed by a 1x1 conv

And in "do lots of computation" section, we could just have a whole bunch of 3x3 convs. But in this case particular, it seems likely that ResNet blocks are going to be better because really the output and the input are very very similar. So we really want a flow through path that allows as little fussing around as possible except a minimal amount necessary to do our super resolution. If we use ResNet blocks, then they have an identity path already. So you can imagine those simple version where it does a bilinear sampling approach or something it could just go through identity block all the way through and then in the upsampling blocks, just learn to take the averages of the inputs and get something that's not too terrible.

So that's what we are going to do. We are going to create something with five ResNet blocks and then for each 2x scale up we have to do, we'll have one upsampling block.

They are all going to consist of, as per usual, convolution layers possibly with activation functions after many of them [00:24:37]. I like to put my standard convolution block into a function so I can refactor it more easily. I won't worry about passing in padding and just calculate it directly as kernel size over two.

def conv(ni, nf, kernel_size=3, actn=False):

"""Standard convolution block"""

layers = [nn.Conv2d(ni, nf, kernel_size, padding=kernel_size//2)]

if actn:

layers.append(nn.ReLU(True))

return nn.Sequential(*layers)

EDSR idea

One interesting thing about our little conv block is that there is no batch norm which is pretty unusual for ResNet type models.

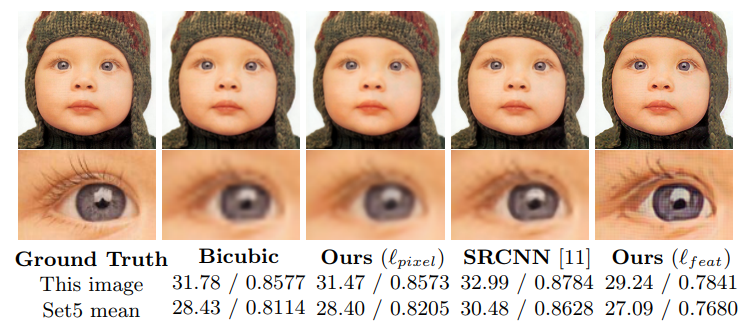

The reason there is no batch norm is because I'm stealing ideas from this fantastic recent paper which actually won a recent competition in super resolution performance. To see how good this paper is, SRResNet is the previous state of the art and what they've done here is they've zoomed way in to an upsampled mesh/fence. HR is the original. You can see in the previous best approach, there's a whole lot of distortion and blurring going on. Or else, in their approach, it's nearly perfect. So this paper was a really big step-up. They call their model EDSR (Enhanced Deep Super-Resolution network) and they did two things differently to the previous standard approaches:

- Take the ResNet blocks and throw away the batch norms. Why would they throw away the batch norm? The reason is because batch norm changes stuff and we want a nice straight through path that doesn't change stuff. So the idea here is if you don't want to fiddle with the input more than you have to, then don't force it to have to calculate things like batch norm parameters — so throw away the batch norm.

- Scaling factor (we will see shortly).

class ResSequential(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, layers, res_scale=1.0):

super().__init__()

self.res_scale = res_scale

self.m = nn.Sequential(*layers)

def forward(self, x):

return x + self.m(x) * self.res_scale

So we are going to create a residual block containing two convolutions. As you see in their approach, they don't even have a ReLU after their second conv. So that's why I've only got activation on the first one.

def res_block(nf):

return ResSequential(

[conv(nf, nf, actn=True), conv(nf, nf)],

0.1)

A couple of interesting things here [00:27:10]. One is that this idea of having some kind of a main ResNet path (conv, ReLU, conv) and then turning that into a ReLU block by adding it back to the identity — it's something we do so often that I factored it out into a tiny little module called ResSequential. It simply takes a bunch of layers that you want to put into your residual path, turns that into a sequential model, runs it, and then adds it back to the input. With this little module, we can now turn anything, like conv activation conv, into a ResNet block just by wrapping in ResSequential.

Batch normalization

But that's not quite all I'm doing because normally a Res block just has x + self.m(x) in its forward. But I've also got * self.res_scale. What's res_scale? res_scale is the number 0.1. Why is it there? I'm not sure anybody quite knows. But the short answer is that the guy (Christian Szegedy) who invented batch norm also somewhat more recently did a paper in which he showed for (I think) the first time the ability to train ImageNet in under an hour. The way he did it was fire up lots and lots of machines and have them work in parallel to create really large batch sizes. Now generally when you increase the batch size by order N, you also increase the learning rate by order N to go with it. So generally a very large batch size training means very high learning rate training as well. He found that with these very large batch sizes of 8,000+ or even up to 32,000, at the start of training, his activations would basicall go straight to infinity. And a lot of other people have found that. We actually found that when we were competing in DAWNBench both on the CIFAR10 and ImageNet competitions that we really struggled to make the most of even the eight GPUs that we were trying to take advantage of because of these challenges with these larger batch sizes and taking advantage of them. Something Christian found was that in the ResNet blocks, if he multiplied them by some number smaller than 1, something like .1 or .2, it really helped stabilize training at the start. That's kind of weird because mathematically, it's identical. Because obviously whatever I'm multiplying it by here, I could just scale the weights by the opposite amount and have the same number. But we are not dealing with abstract math — we are dealing with real optimization problems, different initializations, learning rates, and whatever else. So the problem of weights disappearing off into infinity, I guess generally is really about the discrete and finite nature of computers in practice partly. So often these kind of little tricks can make the difference.

In this case, we are just toning things down based on our initial initialization. So there are probably other ways to do this. For example, one approach from some folks at Nvidia called LARS which I briefly mentioned last week is an approach which uses discriminative learning rates calculated in real time. Basically looking at the ratio between the gradients and the activations to scale learning rates by layer. So they found that they didn't need this trick to scale up the batch sizes a lot. Maybe a different initialization would be all that's necessary. The reason I mentioned this is not so much because I think a lot of you are likely to want to train on massive clusters of computers but rather that I think a lot of you want to train models quickly and that means using high learning rates and ideally getting super convergence. I think these kinds of tricks are the tricks that we'll need to be able to get super convergence across more different architectures and so forth. Other than Leslie Smith, no one else is really working on super convergence other than some fastai students nowadays. So these kind of things about how do we train at very very high learning rates, we're going to have to be the ones who figure it out because as far as I can tell, nobody else cares yet. So looking at the literature around training ImageNet in one hour, or more recently there's now train ImageNet in 15 minutes, these papers actually, I think, have some of the tricks to allow us to train things at high learning rates. So here is one of them.

Interestingly, other than the train ImageNet in one hour paper, the only other place I've seen this mentioned was in this EDSR paper. It's really cool because people who win competitions, I find them to be very pragmatic and well-read. They actually have to get things to work. So this paper describes an approach which actually worked better than anybody else's approach and they did these pragmatic things like throw away batch norm and use this little scaling factor which almost nobody seems to know about. So that's where .1 comes from.

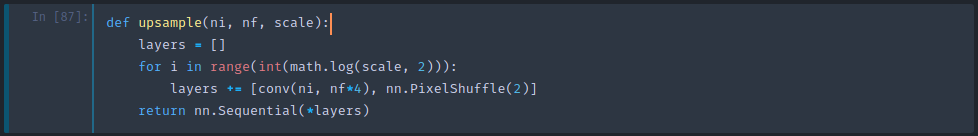

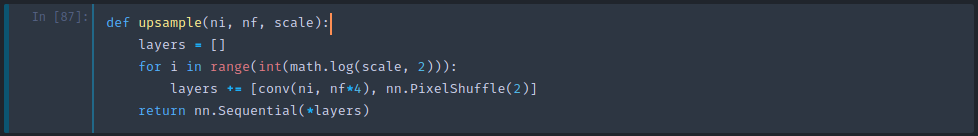

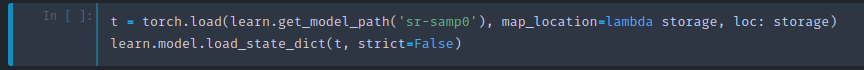

def upsample(ni, nf, scale):

layers = []

for i in range(int(math.log(scale, 2))):

layers += [conv(ni, nf*4), nn.PixelShuffle(2)]

return nn.Sequential(*layers)

So basically our super-resolution ResNet (SrResnet) is going to do a convolution to go from our three channels to 64 channels just to richen up the space a little bit [00:33:25]. Then also we've got actually 8 not 5 Res blocks. Remember, every one of these Res block is stride 1 so the grid size doesn't change, the number of filters doesn't change. It's just 64 all the way through. We'll do one more convolution, and then we'll do our upsampling by however much scale we asked for. Then something I've added which is one batch norm here because it felt like it might be helpful just to scale the last layer. Then finally conv to go back to the three channels we want. So you can see that here's lots and lots of computation and then a little bit of upsampling just like we described.

class SrResnet(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, nf, scale):

super().__init__()

features = [conv(3, 64)]

for i in range(8):

features.append(res_block(64))

features += [

conv(64, 64),

upsample(64, 64, scale),

nn.BatchNorm2d(64),

conv(64, 3)

]

self.features = nn.Sequential(*features)

def forward(self, x):

return self.features(x)

Just to mention, as I'm tending to do now, this whole thing is done by creating a list with layers and then at the end, turning into a sequential model so my forward function is as simple as can be.

Here is our upsampling and upsampling is a bit interesting because it is not doing either of two things (transposed or fractionally strided convolutions or nearest neighbor upsampling followed by a 1x1 conv). So let's talk a bit about upsampling.

Here is the picture from the paper (Perceptual Losses for Real-Time Style Transfer and Super Resolution). So they are saying "hey, our approach is so much better" but look at their approach. It's got artifacts in it. These just pop up everywhere, don't they. One of the reason for this is that they use transposed convolutions and we all know, don't use transposed convolutions.

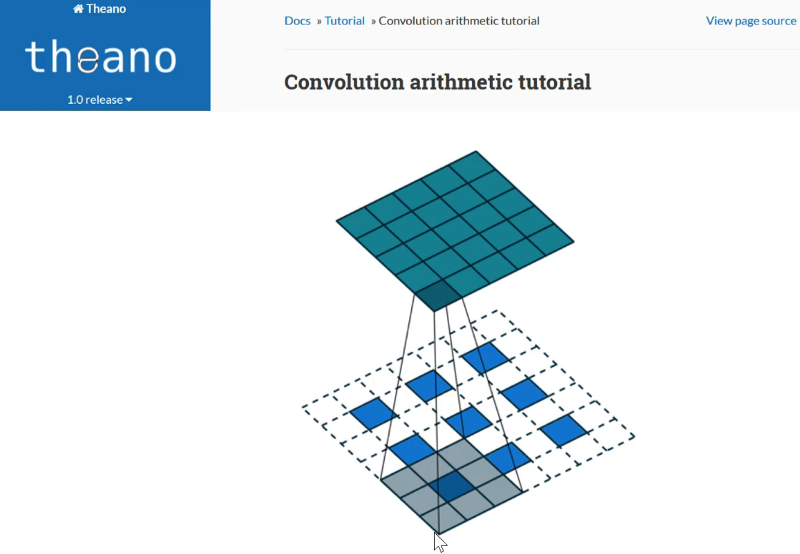

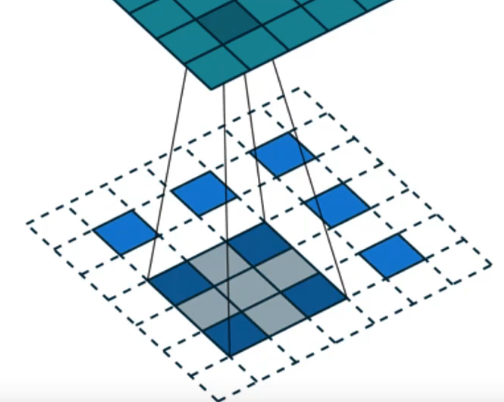

Here are transposed convolutions [00:35:39]. This is from this fantastic convolutional arithmetic paper that was shown also in the Theano docs. If we are going from (blue is the original image) 3x3 image up to a 5x5 image (6x6 if we added a layer of padding), then all a transpose convolution does is it uses a regular 3x3 conv but it sticks white zero pixels between every pair of pixels. That makes the input image bigger and when we run this convolution over it, therefore gives us a larger output. But that's obviously stupid because when we get here, for example, of the nine pixels coming in, eight of them are zero. So we are just wasting a whole a lot of computation. On the other hand, if we are slightly off then four of our nine are non-zero. But yet, we only have one filter/kernel to use so it can't change depending on how many zeros are coming in. So it has to be suitable for both and it's just not possible so we end up with these artifacts.

One approach we've learnt to make it a bit better is to not put white things here but instead to copy the pixel's value to each of these three locations [00:36:53]. So that's a nearest neighbor upsampling. That's certainly a bit better, but it's still pretty crappy because now when we get to these nine (as shown above), 4 of them are exactly the same number. And when we move across one, then now we've got a different situation entirely. So depending on where we are, in particular, if we are here, there's going to be a lot less repetition:

So again, we have this problem where there's wasted computation and too much structure in the data, and it's going to lead to artifacts again. So upsampling is better than transposed convolutions — it's better to copy them rather than replace them with zero. But it's still not quite good enough.

Pixel shuffle

So instead, we are going to do the pixel shuffle [00:37:56]. Pixel shuffle is an operation in this sub-pixel convolutional neural network and it's a little bit mind-bending but it's kind of fascinating.

We start with our input, we go through some convolutions to create some feature maps for a while until eventually we get to layer n[i-1] which has n[i-1] feature maps. We are going to do another 3x3 conv and our goal here is to go from a 7x7 grid cell (we're going to do a 3x3 upscaling) so we are going to go up to a 21x21 grid cell. So what's another way we could do that? To make it simpler, let's just pick one face/layer- so let's take the top most filter and just do a convolution over that just to see what happens. What we are going to do is we are going to use a convolution where the kernel size (the number of filters) is nine times bigger than we need (strictly speaking). So if we needed 64 filters, we are actually going to do 64 times 9 filters. Why? Here, r is the scale factor so 3² is 9, so here are the nine filters to cover one of these input layers/slices. But what we can do is we started with 7x7, and we turned it into 7x7x9. The output that we want is equal to 7 times 3 by 7 times 3. In other words, there is an equal number of pixels/activations here as there are activations in the previous step. So we can literally re-shuffle these 7x7x9 activations to create this 7x3 by 7x3 map [00:40:16]. So what we are going to do is we're going to take one little tube here (all the top left hand of each grid) and we are going to put the purple one up in the top left, then the blue one one to the right, and light blue one on to the right of that, then the slightly darker one in the middle of the far left, the green one in the middle, and so forth. So each of these nine cells in the top left, they are going to end up in the little 3x3 section of our grid. Then we are going to take (2, 1) and take all of those 9 and more them to these 3x3 part of the grid and so on. So we are going to end up having every one of these 7x7x9 activations inside the 7x3 by 7x3 image.

So the first thing to realize is yes of course this works under some definition of works because we have a learnable convolution here and it's going to get some gradients which is going to do the best job it can of filling in the correct activation such that this output is the thing we want. So the first step is to realize there's nothing particularly magical here. We can create any architecture we like. We can move things around anyhow we want to and our weights in the convolution will do their best to do all we asked. The real question is — is it good idea? Is this an easier thing for it to do and a more flexible thing for it to do than the transposed convolution or the upsampling followed by one by one conv? The short answer is yes it is, and the reason it's better in short is that the convolution here is happening in the low resolution 7x7 space which is quite efficient. Or else, if we first of all upsampled and then did our conv then our conv would be happening in the 21 by 21 space which is a lot of computation. Furthermore, as we discussed, there's a lot of replication and redundancy in the nearest neighbor upsample version. They actually show in this paper, in fact, I think they have a follow-up technical note where they provide some more mathematical details as to exactly what work is being done and show that the work really is more efficient this way. So that's what we are going to do. For our upsampling, we have two steps:

- 3x3 conv with r² times more channels than we originally wanted

- Then a pixel shuffle operation which moves everything in each grid cell into the little r by r grids that are located through out here.

So here it is:

It's one line of code. Here is a conv with number of in to number of filters out times four because we are doing a scale two upsample (2²=4). That's our convolution and then here is our pixel shuffle, it's built into PyTorch. Pixel shuffle is the thing that moves each thing into its right spot. So that will upsample by a scale factor of 2. So we need to do that log base 2 scale times. If scale is four, then we'll do two times to go two times two. So that's what this upsample here does.

Checkerboard pattern [00:44:19]

Great. Guess what. That does not get rid of the checkerboard patterns. We still have checkerboard patterns. So I'm sure in great fury and frustration, the same team from Twitter I think this is back when they used to be a startup called Magic Pony that Twitter bought came back again with another paper saying okay, this time we've got rid of the checkerboard.

Why do we still have a checkerboard? The reason we still have a checkerboard even after doing this is that when we randomly initialize this convolutional kernel at the start, it means that each of these 9 pixels in this little 3x3 grid over here are going to be totally randomly different. But then the next set of 3 pixels will be randomly different to each other but will be very similar to their corresponding pixel in the previous 3x3 section. So we are going to have repeating 3x3 things all the way across. Then as we try to learn something better, it's starting from this repeating 3x3 starting point which is not what we want. What we actually would want is for these 3x3 pixels to be the same to start with. To make these 3x3 pixels the same, we would need to make these 9 channels the same here for each filter. So the solution in this paper is very simple. It's that when we initialize this convolution at start when we randomly initialize it, we don't totally randomly initialize it. We randomly initialize one of the r² sets of channels then we copy that to the other r² so they are all the same. That way, initially, each of these 3x3 will be the same. So that is called ICNR (Initialized to Convolution NN Resize) and that's what we are going to use in a moment.

Pixel loss [00:46:41]

Before we do, let's take a quick look. So we've got this super resolution ResNet which just does lots of computation with lots of ResNet blocks and then it does some upsampling and gets our final three channels out.

Parallelize

Then to make life faster, we are going to run things in parallel. One reason we want to run it in parallel is because Gerardo told us that he has 6 GPUs and this is what his computer looks like right now. 😆

So I'm sure anybody who has more than one GPU has had this experience before. So how do we get these men working together? All you need to do is to take your PyTorch module and wrap it with nn.DataParallel. Once you've done that, it copies it to each of your GPUs and will automatically run it in parallel. It scales pretty well to two GPUs, okay to three GPUs, better than nothing to four GPUs and beyond that, performance does go backwards. By default, it will copy it to all of your GPUs — you can add an array of GPUs otherwise if you want to avoid getting in trouble, for example, I have to share our box with Yannet and if I didn't put this here, then she would be yelling at me right now or boycotting my class. So this is how you avoid getting into trouble with Yannet.

m = to_gpu(SrResnet(64, scale))

# Uncomment this line if you have more than 1 GPU.

m = nn.DataParallel(m, [0, 2])

learn = Learner(md, SingleModel(m), opt_fn=optim.Adam)

learn.crit = F.mse_loss

One thing to be aware of here is that once you do this, it actually modifies your module [00:48:21]. So if you now print out your module, let's say previously it was just an endless sequential, now you'll find it's an nn.Sequential embedded inside a module called Module. In other words, if you save something which you had nn.DataParallel and then tried and load it back into something you haven't nn.DataParallel, it'll say it doesn't match up because one of them is embedded inside this Module attribute and the other one isn't. It may also depend even on which GPU IDs you have had it copy to. Two possible solutions:

- Don't save the module

mbut instead save the module attributem.modulebecause that's actually the non data parallel bit. - Always put it on the same GPU IDs and then use data parallel and load and save that every time. That's what I was using.

This is an easy thing for me to fix automatically in fast.ai and I'll do it pretty soon so it will look for that module attribute and deal with it automatically. But for now, we have to do it manually. It's probably useful to know what's going on behind the scenes anyway.

So we've got our module [00:49:46]. I find it'll run 50 or 60% faster on a 1080 Ti, if you are running on Volta, it actually parallelize a bit better. There are much faster ways to parallelize but this is a super easy way.

Loss function and training

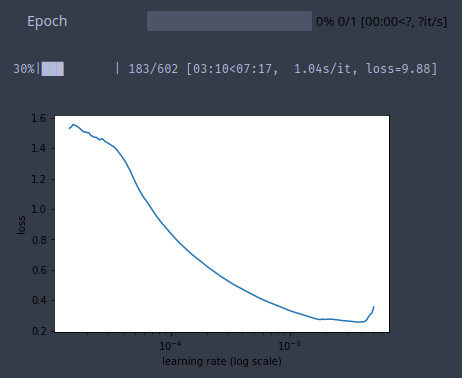

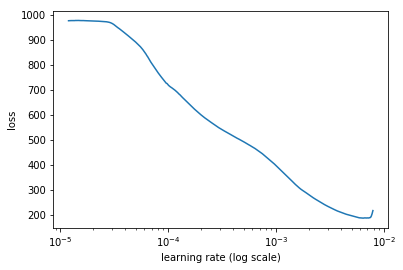

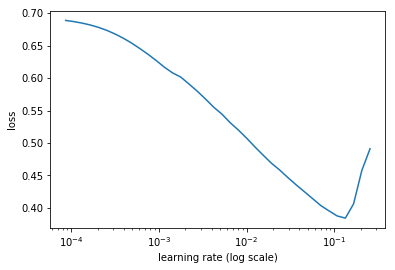

We create our learner in the usual way. We can use MSE loss here so that's just going to compare the pixels of the output to the pixels that we expected. We can run our learning rate finder and we can train it for a while.

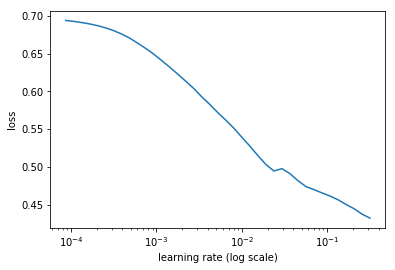

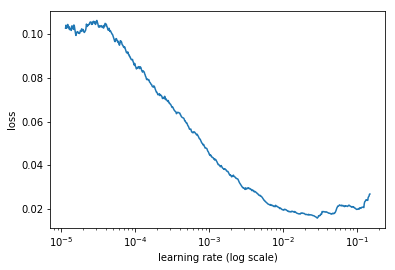

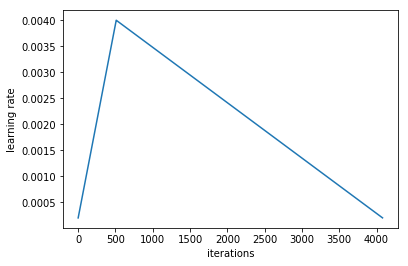

learn.lr_find(start_lr=1e-5, end_lr=10000)

learn.sched.plot(10, 0)

# -----------------------------------------------------------------------------

# Output

# -----------------------------------------------------------------------------

30%|███ | 183/602 [03:10<07:17, 1.04s/it, loss=9.88]

lr = 2e-3

learn.fit(lr, 1, cycle_len=1, use_clr_beta=(40, 10))

# -----------------------------------------------------------------------------

# Output

# -----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Epoch 100% 1/1 [09:48<00:00, 588.53s/it]

epoch trn_loss val_loss

0 0.103036 0.09909

[array([0.09909])]

x,y = next(iter(md.val_dl))

preds = learn.model(VV(x))

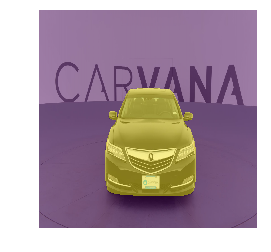

Here is our input:

idx = 1

show_img(y, idx, normed=True)

And here is our output.

show_img(preds, idx, normed=True)

And you can see that what we've managed to do is to train a very advanced residual convolutional network that's learnt to blur things. Why is that? Well, because it's what we asked for. We said to minimize MSE loss. MSE loss between pixels really the best way to do that is just average the pixel i.e. to blur it. So that's why pixel loss is no good. So we want to use our perceptual loss.

show_img(x, idx, normed=True)

idx = 2

# Ground truth image (high-res)

show_img(y, idx, normed=True)

# # Upsampled image (output)

show_img(preds, idx, normed=True)

# Input image (low-res)

show_img(x, idx, normed=True)

Perceptual loss [00:50:57]

With perceptual loss, we are basically going to take our VGG network and just like we did last week, we are going to find the block index just before we get a maxpool.

def icnr(x, scale=2, init=nn.init.kaiming_normal):

new_shape = [int(x.shape[0] / (scale ** 2))] + list(x.shape[1:])

subkernel = torch.zeros(new_shape)

subkernel = init(subkernel)

subkernel = subkernel.transpose(0, 1)

subkernel = subkernel.contiguous().view(subkernel.shape[0],

subkernel.shape[1], -1)

kernel = subkernel.repeat(1, 1, scale ** 2)

transposed_shape = [x.shape[1]] + [x.shape[0]] + list(x.shape[2:])

kernel = kernel.contiguous().view(transposed_shape)

kernel = kernel.transpose(0, 1)

return kernel

m_vgg = vgg16(True)

blocks = [i - 1 for i, o in enumerate(children(m_vgg))

if isinstance(o, nn.MaxPool2d)]

blocks, [m_vgg[i] for i in blocks]

# -----------------------------------------------------------------------------

# Output

# -----------------------------------------------------------------------------

([5, 12, 22, 32, 42],

[ReLU(inplace), ReLU(inplace), ReLU(inplace), ReLU(inplace), ReLU(inplace)])

So here are the ends of each block of the same grid size. If we just print them out, as we'd expect, every one of those is a ReLU module and so in this case these last two blocks are less interesting to us. The grid size there is small enough, and course enough that it's not as useful for super resolution. So we are just going to use the first three. Just to save unnecessary computation, we are just going to use those first 23 layers of VGG and we'll throw away the rest. We'll stick it on the GPU. We are not going to be training this VGG model at all — we are just using it to compare activations. So we'll stick it in eval mode and we will set it to not trainable.

vgg_layers = children(m_vgg)[:23]

m_vgg = nn.Sequential(*vgg_layers).cuda().eval()

set_trainable(m_vgg, False)

def flatten(x): return x.view(x.size(0), -1)

Just like last week, we will use SaveFeatures class to do a forward hook which saves the output activations at each of those layers [00:52:07].

class SaveFeatures():

features=None

def __init__(self, m): self.hook = m.register_forward_hook(self.hook_fn)

def hook_fn(self, module, input, output): self.features = output

def remove(self): self.hook.remove()

So now we have everything we need to create our perceptual loss or as I call it here FeatureLoss class. We are going to pass in a list of layer IDs, the layers where we want the content loss to be calculated, and a list of weights for each of those layers. We can go through each of those layer IDs and create an object which has the forward hook function to store the activations. So in our forward, then we can just go ahead and call the forward pass of our model with the target (high res image we are trying to create). The reason we do that is because that is going to then call that hook function and store in self.sfs (self dot save features) the activations we want. Now we are going to need to do that for our conv net output as well. So we need to clone these because otherwise the conv net output is going to go ahead and just clobber what I already had. So now we can do the same thing for the conv net output which is the input to the loss function. And so now we've got those two things we can zip them all together along with the weights so we've got inputs, targets, and weights. Then we can do the L1 loss between the inputs and the targets and multiply by the layer weights. The only other thing I do is I also grab the pixel loss, but I weight it down quite a bit. Most people don't do this. I haven't seen papers that do this, but in my opinion, it's maybe a little bit better because you've got the perceptual content loss activation stuff but the really finest level it also cares about the individual pixels. So that's our loss function.

class FeatureLoss(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, m, layer_ids, layer_wgts):

super().__init__()

self.m, self.wgts = m, layer_wgts

self.sfs = [SaveFeatures(m[i]) for i in layer_ids]

def forward(self, input, target, sum_layers=True):

self.m(VV(target.data))

res = [F.l1_loss(input, target) / 100]

targ_feat = [V(o.features.data.clone()) for o in self.sfs]

self.m(input)

res += [F.l1_loss(flatten(inp.features), flatten(targ)) * wgt

for inp, targ, wgt in zip(self.sfs, targ_feat, self.wgts)]

if sum_layers: res = sum(res)

return res

def close(self):

for o in self.sfs: o.remove()

We create our super resolution ResNet telling it how much to scale up by.

m = SrResnet(64, scale)

And then we are going to do our icnr initialization of that pixel shuffle convolution [00:54:27]. This is very boring code, I actually stole it from somebody else. Literally all it does is just say okay, you've got some weight tensor x that you want to initialize so we are going to treat it as if it has shape (i.e. number of features) divided by scale squared features in practice. So this might be 2² = 4 because we actually want to just keep one set of then and then copy them four times, so we divide it by four and we create something of that size and we initialize that with, by default, kaiming_normal initialization. Then we just make scale² copies of it. And the rest of it is just kind of moving axes around a little bit. So that's going to return a new weight matrix where each initialized sub kernel is repeated r² or scale² times. So that details don't matter very much. All that matters here is that I just looked through to find what was the actual conv layer just before the pixel shuffle and store it away and then I called icnr on its weight matrix to get my new weight matrix. And then I copied that new weight matrix back into that layer.

conv_shuffle = m.features[10][0][0]

kernel = icnr(conv_shuffle.weight, scale=scale)

conv_shuffle.weight.data.copy_(kernel)

As you can see, I went to quite a lot of trouble in this exercise to really try to implement all the best practices [00:56:13]. I tend to do things a bit one extreme or the other. I show you a really hacky version that only slightly works or I go to the nth degree to make it work really well. So this is a version where I'm claiming that this is pretty much a state of the art implementation. It's a competition winning or at least my re-implementation of a competition winning approach. The reason I'm doing that is because I think this is one of those rare papers where they actually get a lot of the details right and I want you to get a feel of what it feels like to get all the details right. Remember, getting the details right is the difference between the hideous blurry mess and the pretty exquisite result.

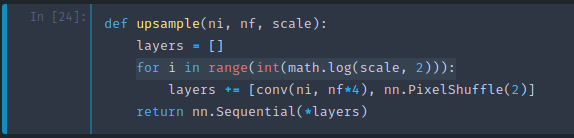

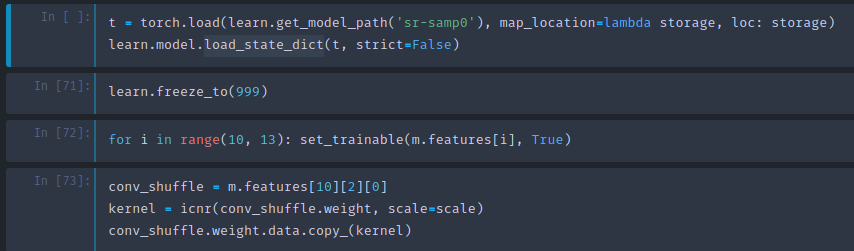

m = to_gpu(m)

learn = Learner(md, SingleModel(m), opt_fn=optim.Adam)

t = torch.load(learn.get_model_path('sr-samp0'),

map_location=lambda storage, loc: storage)

learn.model.load_state_dict(t, strict=False)

learn.freeze_to(999)

for i in range(10, 13): set_trainable(m.features[i], True)

conv_shuffle = m.features[10][2][0]

kernel = icnr(conv_shuffle.weight, scale=scale)

conv_shuffle.weight.data.copy_(kernel)

So we are going do DataParallel on that again [00:57:14].

# m = nn.DataParallel(m, [0, 2])

learn = Learner(md, SingleModel(m), opt_fn=optim.Adam)

learn.set_data(md)

We are going to set our criterion to be FeatureLoss using our VGG model, grab the first few blocks and these are sets of layer weights that I found worked pretty well.

learn.crit = FeatureLoss(m_vgg, blocks[:3], [0.2, 0.7, 0.1])

lr = 6e-3

wd = 1e-7

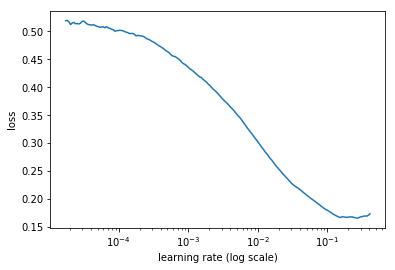

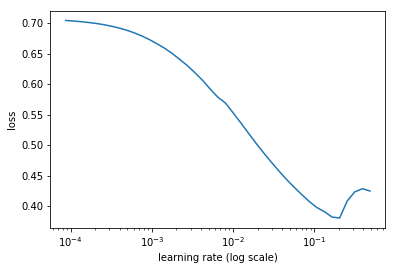

Do a learning rate finder.

%time learn.lr_find(1e-4, 0.1, wds=wd, linear=True)

# -----------------------------------------------------------------------------

# Output

# -----------------------------------------------------------------------------

12%|█▏ | 71/602 [03:10<23:44, 2.68s/it, loss=0.807]

CPU times: user 4min 32s, sys: 17.9 s, total: 4min 50s

Wall time: 3min 10s

learn.sched.plot(n_skip_end=1)

Fit it for a while.

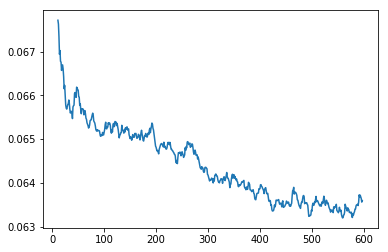

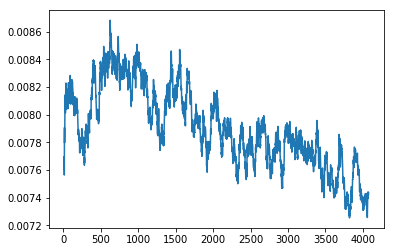

learn.fit(lr, 1, cycle_len=2, wds=wd, use_clr=(20, 10))

# -----------------------------------------------------------------------------

# Output

# -----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Epoch 100% 2/2 [52:34<00:00, 1577.27s/it]

epoch trn_loss val_loss

0 0.06387 0.062875

1 0.062231 0.060575

[array([0.06057])]

learn.save('sr-samp0')

And I fiddled around for a while trying to get some of these details right. But here is my favorite part of the paper is what happens next. Now that we've done it for scale equals 2 — progressive resizing. So progressive resizing is the trick that let us get the best best single computer result for ImageNet training on DAWNBench. It's this idea of starting small gradually making bigger. I only know of two papers that have used this idea. One is the progressive resizing of GANs paper which allows training a very high resolution GANs and the other one is the EDSR paper. And the cool thing about progressive resizing is not only are your earlier epochs, assuming you've got 2x2 smaller, four times faster. You can also make the batch size maybe 3 or 4 times bigger. But more importantly, they are going to generalize better because you are feeding in your model different sized images during training. So we were able to train half as many epochs for ImageNet as most people. Our epochs were faster and there were fewer of them. So progressive resizing is something that, particularly if you are training from scratch (I'm not so sure if it's useful for fine-tuning transfer learning, but if you are training from scratch), you probably want to do nearly all the time.

Progressive resizing [00:59:07]

So the next step is to go all the way back to the top and change to 4 scale, 32 batch size, restart. I saved the model before I do that.

Go back and that's why there's a little bit of fussing around in here with reloading because what I needed to do now is I needed to load my saved model back in.

But there's a slight issue which is I now have one more upsampling layer than I used to have to go from 2x2 to 4x4. My loop here is now looping through twice, not once. Therefore, it's added an extra conv net and an extra pixel shuffle. So how am I going to load in weights for a different network?

The answer is that I use a very handy thing in PyTorch load_state_dict. This is what learner.load calls behind the scenes. If I pass this parameter strict=False then it says "okay, if you can't fill in all of the layers, just fill in the layers you can." So after loading the model back in this way, we are going to end up with something where it's loaded in all the layers that it can and that one conv layer that's new is going to be randomly initialized.

Then I freeze all my layers and then unfreeze that upsampling part [1:00:45] Then use icnr on my newly added extra layer. Then I can go ahead and learn again. So then the rest is the same.

If you are trying to replicate this, don't just run this top to bottom. Realize it involves a bit of jumping around.

learn.load('sr-samp1')

lr = 3e-3

learn.fit(lr, 1, cycle_len=1, wds=wd, use_clr=(20, 10))

# -----------------------------------------------------------------------------

# Output

# -----------------------------------------------------------------------------

epoch trn_loss val_loss

0 0.069054 0.06638

[array([0.06638])]

learn.save('sr-samp2')

learn.unfreeze()

learn.load('sr-samp2')

learn.fit(lr / 3, 1, cycle_len=1, wds=wd, use_clr=(20, 10))

# -----------------------------------------------------------------------------

# Output

# -----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Epoch 100% 1/1 [26:22<00:00, 1582.05s/it]

epoch trn_loss val_loss

0 0.063521 0.060426

[array([0.06043])]

learn.save('sr1')

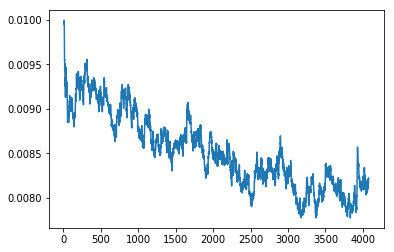

learn.sched.plot_loss()

def plot_ds_img(idx, ax=None, figsize=(7, 7), normed=True):

if ax is None: fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=figsize)

im = md.val_ds[idx][0]

if normed: im = denorm(im)[0]

else: im = np.rollaxis(to_np(im), 0, 3)

ax.imshow(im)

ax.axis('off')

fig, axes = plt.subplots(6, 6, figsize=(20, 20))

for i, ax in enumerate(axes.flat):

plot_ds_img(i + 35, ax=ax, normed=True)

x, y = md.val_ds[215]

y = y[None]

learn.model.eval()

preds = learn.model(VV(x[None]))

x.shape, y.shape, preds.shape

# -----------------------------------------------------------------------------

# Output

# -----------------------------------------------------------------------------

((3, 72, 72), (1, 3, 288, 288), torch.Size([1, 3, 288, 288]))

learn.crit(preds, V(y), sum_layers=False)

# -----------------------------------------------------------------------------

# Output

# -----------------------------------------------------------------------------

[Variable containing:

1.00000e-03 *

1.3694

[torch.cuda.FloatTensor of size 1 (GPU 0)], Variable containing:

1.00000e-02 *

1.0221

[torch.cuda.FloatTensor of size 1 (GPU 0)], Variable containing:

1.00000e-02 *

3.9270

[torch.cuda.FloatTensor of size 1 (GPU 0)], Variable containing:

1.00000e-03 *

3.9834

[torch.cuda.FloatTensor of size 1 (GPU 0)]]

learn.crit.close()

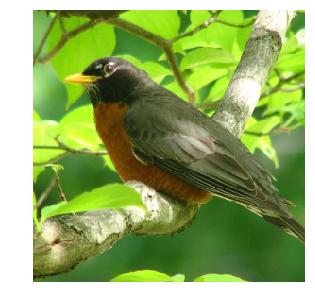

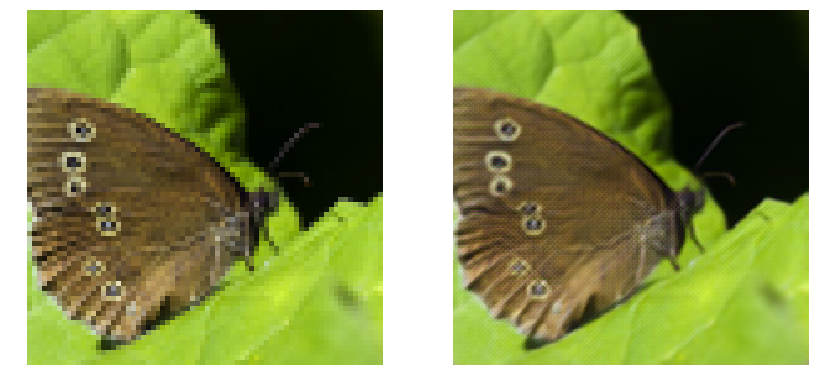

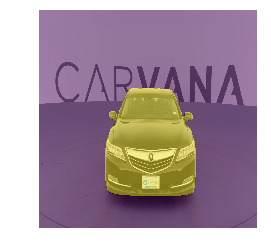

The longer you train, the better it gets [1:01:18]. I ended up training it for about 10 hours, but you'll still get very good results much more quickly if you're less patient. So we can try it out and and here is the result. On the left is my pixelated bird and on the right is the upsampled version. It literally invented coloration. But it figured out what kind of bird it is, and it knows what these feathers are meant to look like. So it has imagined a set of feathers which are compatible with these exact pixels which is genius. Same for the back of its head. There is no way you can tell what these blue dots are meant to represent. But if you know that this kind of bird has an array of feathers here, you know that's what they must be. Then you can figure out whether the feathers would have to be such that when they were pixelated they would end up in these spots. So it literally reverse engineered given its knowledge of this exact species of bird, how it would have to have looked to create this output. This is so amazing. It also knows from all the signs around it that this area here (background) was almost certainly blurred out. So it actually reconstructed blurred vegetation. If it hadn't have done all of those things, it wouldn't have gotten such a good loss function. Because in the end, it had to match the activations saying "oh, there's a feather over here and it's kind of fluffy looking and it's in this direction" and all that.

_, axes = plt.subplots(1, 2, figsize=(14, 7))

show_img(x[None], 0, ax=axes[0])

show_img(preds, 0, normed=True, ax=axes[1])

Well, that brings us to the end of super resolution [1:03:18]. Don't forget to check out the ask Jeremy anything thread.

Ask Jeremy Anything

❓ What are the future plans for fast.ai and this course? Will there be a part 3? If there is a part 3, I would really love to take it [1:04:11].

Jeremy: I'm not quite sure. It's always hard to guess. I hope there will be some kind of follow-up. Last year, after part 2, one of the students started up a weekly book club going through the Ian Goodfellow Deep Learning book, and Ian actually came in and presented quite a few of the chapters and there was somebody, an expert, who presented every chapter. That was a really cool part 3. To a large extent, it will depend on you, the community, to come up with ideas and help make them happen, and I'm definitely keen to help. I've got a bunch of ideas but I'm nervous about saying them because I'm not sure which ones will happen and which ones won't. But the more support I have in making things happen that you want to happen from you, the more likely they are to happen.

❓ What was your experience like starting down the path of entrepreneurship? Have you always been an entrepreneur or did you start at a big company and transition to a startup? Did you go from academia to startups or startups to academia? [1:05:13]

Jeremy: No, I was definitely not an academia. I am totally a fake academic. I started at McKinsey and company which is a strategy firm when I was 18 which meant I couldn't really go to university so it didn't really turn up. Then spent 8 years in business helping really big companies on strategic questions. I always wanted to be an entrepreneur, planned to only spend two years in McKinsey, only thing I really regret in my life was not sticking to that plan and wasting eight years instead. So two years would have been perfect. But then I went into entrepreneurship, started two companies in Australia. The best part about that was that I didn't get any funding so all the money that I made was mine or the decisions were mine and my partner's. I focused entirely on profit and product and customer and service. Whereas I find in San Francisco, I'm glad I came here and so the two of us came here for Kaggle, Anthony and I, and raised ridiculous amount of money 11 million dollar for this really new company. That was really interesting but it's also really distracting trying to worry about scaling and VC's wanting to see what your business development plans are and also just not having any real need to actually make a profit. So I had a bit of the same problem at Enlitic where I again raised a lot of money 15 million dollars pretty quickly and a lot of distractions. I think trying to bootstrap your own company and focus on making money by selling something at a profit and then plowing that back into the company, it worked really well. Because within five years, we were making a profit from 3 months in and within 5 years, we were making enough for profit not just to pay all of us and our own wages but also to see my bank account growing and after 10 years sold it for a big chunk of money, not enough that a VC would be excited but enough that I didn't have to worry about money again. So I think bootstrapping a company is something which people in the Bay Area at least don't seem to appreciate how good of an idea that is.

❓ If you were 25 years old today and still know what you know where would you be looking to use AI? What are you working on right now or looking to work on in the next 2 years [1:08:10]?

Jeremy: You should ignore the last part of that. I won't even answer it. Doesn't matter where I'm looking. What you should do is leverage your knowledge about your domain. So one of the main reasons we do this is to get people who have backgrounds in recruiting, oil field surveys, journalism, activism, whatever and solve your problems. It'll be really obvious to you what real problems are and it will be really obvious to you what data you have and where to find it. Those are all the bits that for everybody else that's really hard. So people who start out with "oh, I know deep learning now I'll go and find something to apply it to" basically never succeed where else people who are like "oh, I've been spending 25 years doing specialized recruiting for legal firms and I know that the key issue is this thing and I know that this piece of data totally solves it and so I'm just going to do that now and I already know who to call or actually start selling it to". They are the ones who tend to win. If you've done nothing but academic stuff, then it's more maybe about your hobbies and interests. So everybody has hobbies. The main thing I would say is please don't focus on building tools for data scientists to use or for software engineers to use because every data scientist knows about the market of data scientists whereas only you know about the market for analyzing oil survey world or understanding audiology studies or whatever it is that you do.

❓ Given what you've shown us about applying transfer learning from image recognition to NLP, there looks to be a lot of value in paying attention to all of the developments that happen across the whole ML field and that if you were to focus in one area you might miss out on some great advances in other concentrations. How do you stay aware of all of the advancements across the field while still having time to dig in deep to your specific domains [1:10:19]?

Jeremy: Yeah, that's awesome. I mean that's one of the key messages of this course. Lots of good work's being done in different places and people are so specialized and most people don't know about it. If I can get state of the art results in NLP within six months of starting to look at NLP and I think that says more about NLP than it does about me, frankly. It's kind of like the entrepreneurship thing. You pick the areas you see that you know about and kind of transfer stuff like "oh, we could use deep learning to solve this problem" or in this case, we could use this idea of computer vision to solve that problem. So things like transfer learning, I'm sure there's like a thousand opportunities for you to do in other field to do what Sebastian and I did in NLP with NLP classification. So the short answer to your question is the way to stay ahead of what's going on would be to follow my feed of Twitter favorites and my approach is to then follow lots and lots of people on Twitter and put them into the Twitter favorites for you. Literally, every time I come across something interesting, I click favorite. There are two reasons I do it. The first is that when the next course comes along, I go through my favorites to find which things I want to study. The second is so that you can do the same thing. And then which you go deep into, it almost doesn't matter. I find every time I look at something it turns out to be super interesting and important. So pick something which you feel like solving that problem would be actually useful for some reason and it doesn't seem to be very popular which is kind of the opposite of what everybody else does. Everybody else works on the problems which everybody else is already working on because they are the ones that seem popular. I can't quite understand this train of thinking but it seems to be very common.

❓ Is Deep Learning an overkill to use on Tabular data? When is it better to use DL instead of ML on tabular data [1:12:46]?

Jeremy: Is that a real question or did you just put that there so that I would point out that Rachel Thomas just wrote an article? http://www.fast.ai/2018/04/29/categorical-embeddings/

So Rachel has just written about this and Rachel and I spent a long time talking about it and the short answer is we think it's great to use deep learning on tabular data. Actually, of all the rich complex important and interesting things that appear in Rachel's Twitter stream covering everything from the genocide of Rohingya through to latest ethics violations in AI companies, the one by far that got the most attention and engagement from the community was the question about is it called tabular data or structured data. So yeah, ask computer people how to name things and you'll get plenty of interest. There are some really good links here to stuff from Instacart and Pinterest and other folks who have done some good work in this area. Any of you that went to the Data Institute conference would have seen Jeremy Stanley's presentation about the really cool work they did at Instacart.

Rachel: I relied heavily on lessons 3 and 4 from part 1 in writing this post so much of that may be familiar to you.

Jeremy: Rachel asked me during the post like how to tell whether you should use the decision tree ensemble like GBM or random forest or neural net and my answer is I still don't know. Nobody I'm aware of has done that research in any particularly meaningful way. So there's a question to be answered there, I guess. My approach has been to try to make both of those things as accessible as possible through fast.ai library so you can try them both and see what works. That's what I do.

❓ Reinforcement Learning popularity has been on a gradual rise in the recent past. What's your take on Reinforcement Learning? Would fast.ai consider covering some ground in popular RL techniques in the future [1:15:21]?

Jeremy: I'm still not a believer in reinforcement learning. I think it's an interesting problem to solve but it's not at all clear that we have a good way of solving this problem. So the problem, it really is the delayed credit problem. So I want to learn to play pong, I've moved up or down and three minutes later I find out whether I won the game of pong — which actions I took were actually useful? So to me, the idea of calculating the gradients of the output with respect to those inputs, the credit is so delayed that those derivatives don't seem very interesting. I get this question quite regularly in every one of these four courses so far. I've always said the same thing. I'm rather pleased that finally recently there's been some results showing that actually basically random search often does better than reinforcement learning so basically what's happened is very well-funded companies with vast amounts of computational power throw all of it at reinforcement learning problems and get good results and people then say "oh it's because of the reinforcement learning" rather than the vast amounts of compute power. Or they use extremely thoughtful and clever algorithms like a combination of convolutional neural nets and Monte Carlo tree search like they did with the Alpha Go stuff to get great results and people incorrectly say "oh that's because of reinforcement learning" when it wasn't really reinforcement learning at all. So I'm very interested in solving these kind of more generic optimization type problems rather than just prediction problems and that's what these delayed credit problems tend to look like. But I don't think we've yet got good enough best practices that I have anything on, ready to teach and say I've got to teach you this thing because I think it's still going to be useful next year. So we'll keep watching and see what happens.

Super resolution network to a style transfer network [01:17:57]

We are going to now turn the super resolution network into a style transfer network. And we'll do this pretty quickly. We basically already have something. x is my input image and I'm going to have some loss function and I've got some neural net again. Instead of a neural net that does a whole a lot of compute and then does upsampling at the end, our input this time is just as big as our output. So we are going to do some downsampling first. Then our computer, and then our upsampling. So that's the first change we are going to make — we are going to add some downsampling so some stride 2 convolution layers to the front of our network. The second is rather than just comparing yc and x are the same thing here. So we are going to basically say our input image should look like itself by the end. Specifically we are going to compare it by chucking it through VGG and comparing it at one of the activation layers. And then its style should look like some painting which we'll do just like we did with the Gatys' approach by looking at the Gram matrix correspondence at a number of layers. So that's basically it. So that ought to be super straight forward. It's really combining two things we've already done.

Style transfer network [01:19:19]

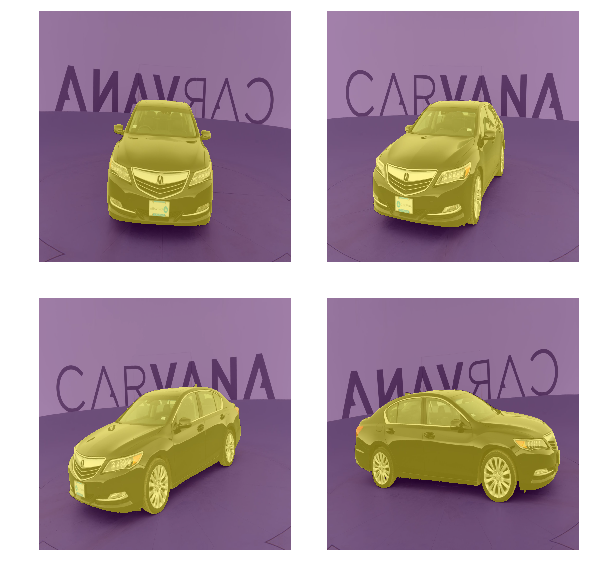

So all this code starts identical, except we don't have high res and low res, we just have one size 256.

%matplotlib inline

%reload_ext autoreload

%autoreload 2

from fastai.conv_learner import *

from pathlib import Path

# torch.cuda.set_device(0)

torch.backends.cudnn.benchmark = True

PATH = Path('data/imagenet')

PATH_TRN = PATH / 'train'

fnames_full, label_arr_full, all_labels = folder_source(PATH, 'train')

fnames_full = ['/'.join(Path(fn).parts[-2:]) for fn in fnames_full]

list(zip(fnames_full[:5], label_arr_full[:5]))

# -----------------------------------------------------------------------------

# Output

# -----------------------------------------------------------------------------

[('n01440764/n01440764_12241.JPEG', 0),

('n01440764/n01440764_529.JPEG', 0),

('n01440764/n01440764_11155.JPEG', 0),

('n01440764/n01440764_9649.JPEG', 0),

('n01440764/n01440764_8013.JPEG', 0)]

all_labels[:5]

# -----------------------------------------------------------------------------

# Output

# -----------------------------------------------------------------------------

['n01440764', 'n01443537', 'n01491361', 'n01494475', 'n01498041']

np.random.seed(42)

keep_pct = 1.

# keep_pct = 0.1

keeps = np.random.rand(len(fnames_full)) < keep_pct

fnames = np.array(fnames_full, copy=False)[keeps]

label_arr = np.array(label_arr_full, copy=False)[keeps]

arch = vgg16

# sz, bs = 96, 32

sz, bs = 256, 24

# sz, bs = 128, 32

class MatchedFilesDataset(FilesDataset):

def __init__(self, fnames, y, transform, path):

self.y = y

assert(len(fnames) == len(y))

super().__init__(fnames, transform, path)

def get_y(self, i): return open_image(os.path.join(self.path, self.y[i]))

def get_c(self): return 0

val_idxs = get_cv_idxs(len(fnames), val_pct=min(0.01/keep_pct, 0.1))

((val_x, trn_x), (val_y, trn_y)) = split_by_idx(val_idxs, np.array(fnames), np.array(fnames))

len(val_x), len(trn_x)

# -----------------------------------------------------------------------------

# Output

# -----------------------------------------------------------------------------

(194, 19245)

img_fn = PATH / 'train' / 'n01558993' / 'n01558993_9684.JPEG'

tfms = tfms_from_model(arch, sz, tfm_y=TfmType.PIXEL)

datasets = ImageData.get_ds(MatchedFilesDataset, (trn_x, trn_y), (val_x, val_y), tfms, path=PATH_TRN)

md = ImageData(PATH, datasets, bs, num_workers=16, classes=None)

denorm = md.val_ds.denorm

def show_img(ims, idx, figsize=(5, 5), normed=True, ax=None):

if ax is None: fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=figsize)

if normed: ims = denorm(ims)

else: ims = np.rollaxis(to_np(ims), 1, 4)

ax.imshow(np.clip(ims, 0, 1)[idx])

ax.axis('off')

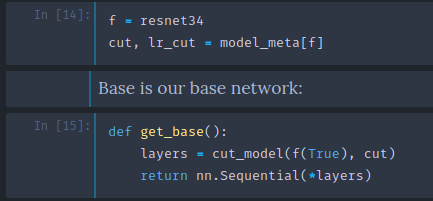

Model [01:19:30]

My model is the same. One thing I did here is I did not do any kind of fancy best practices for this one at all. Partly because there doesn't seem to be any. There's been very little follow up in this approach compared to the super resolution stuff. We'll talk about why in a moment. So you'll see, this is much more normal looking.

def conv(ni, nf, kernel_size=3, stride=1, actn=True, pad=None, bn=True):

if pad is None: pad = kernel_size//2

layers = [nn.Conv2d(ni, nf, kernel_size, stride=stride, padding=pad, bias=not bn)]

if actn: layers.append(nn.ReLU(inplace=True))

if bn: layers.append(nn.BatchNorm2d(nf))

return nn.Sequential(*layers)

I've got batch norm layers. I don't have scaling factor here.

class ResSequentialCenter(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, layers):

super().__init__()

self.m = nn.Sequential(*layers)

def forward(self, x): return x[:, :, 2:-2, 2:-2] + self.m(x)

def res_block(nf):

return ResSequentialCenter([conv(nf, nf, actn=True, pad=0), conv(nf, nf, pad=0)])

I don't have a pixel shuffle — it's just using a normal upsampling followed by 1x1 conf. So it's just more normal.

def upsample(ni, nf):

return nn.Sequential(nn.Upsample(scale_factor=2), conv(ni, nf))

One thing they mentioned in the paper is they had a lot of problems with zero padding creating artifacts and the way they solved that was by adding 40 pixel of reflection padding at the start. So I did the same thing and then they used zero padding in their convolutions in their Res blocks. Now if you've got zero padding in your convolutions in your Res blocks, then that means that the two parts of your ResNet won't add up anymore because you've lost a pixel from each side on each of your two convolutions. So my ResSequential has become ResSequentialCenter and I've removed the last 2 pixels on each side of those good cells. Other than that, this is basically the same as what we had before.

class StyleResnet(nn.Module):

def __init__(self):

super().__init__()

features = [

nn.ReflectionPad2d(40),

conv(3, 32, 9),

conv(32, 64, stride=2),

conv(64, 128, stride=2)

]

for i in range(5):

features.append(res_block(128))

features += [

upsample(128, 64),

upsample(64, 32),

conv(32, 3, 9, actn=False)

]

self.features = nn.Sequential(*features)

def forward(self, x):